I became a vegetarian when I was fourteen. This was an uncomfortable decision as I grew up in a rural farming community, spent much of my childhood playing and occasionally helping out on friends farms. My family isn’t very far away from farming, my grandparents grew up on farms. Almost everyone I knew found my decision a little odd and they struggled to get their heads around it. I love the farming community, like many growing up in a rural area I was involved with a local YFC [Young Farmers Club], it is the land I grew up in. Whilst I was clearly different, seen as a leftie and had a sandal on one foot, my other foot stayed in a wellie, happy to be out in the mud.

What had caused this fairly radical decision was learning about intensive farming. That some of the meat I ate came from animals reared indoors on feed grown with artificial fertilisers and pesticides on giant fields with no relation to the small family farms of my area. Whilst I was happy to eat from the traditionally reared animals, who grazed outside on local farms, I was deeply unhappy about eating meat from intensive production. Everyone else seemed less troubled by this, though noone, somewhat oddly, was hostile, I was being agreed with to an extent, I only rarely suffered from the ‘bloody vegetarians’ jibe. As a fourteen year old, I wasn’t responsible for the food on my table, so the only way I could guarantee not eating food I objected to was to go vegetarian.

My parents attitude was that this was just a ‘phase’ and they said this was fine if you cook your own meals, so I learnt how to cook. I didn’t look back as this allowed to to experiment and discover interesting tasty meals. A few years later I left home for a big city, where butchers shops were already dying and people were almost exclusively buying meat from supermarkets, with scant labelling as to production methodology, this at least made my life easier as I didn’t even know how to get meat I was happy with. I couldn’t understand why no-one else was as troubled by my dilemma around food.

I then felt a pressure to go vegan. It seemed you either support farming or went vegan, there is no middle ground or place for a ‘fence sitter’ such as myself. I was still buying milk, because in Britain at the time most milk was still from pasture based producution from small farms and cheese would have been even harder to give up, I love blue cheeses. As the years past this was changing, the small dairy farms and dairies were disappearing rapidly, I needed to make a decision about milk.

In the 90s there was a craze for organic produce, it even became available in the supermarkets. Organic production standards require animals to graze on pasture, so in organic milk I could be assured, so took the decision to only buy organic milk. I also took the decision, to start eating organic meat. I’d never objected to killing animals for food, I grew up in the countryside amongst natures continuing cycle of birth and death. I’ve never intentionally killed an animal myself, I’ve hit the odd rabbit or badger with my car and I have seen people and animals die in front of me.

The thing was I was now a competent vegan cook and hadn’t eaten meat for fourteen years. I’d been brought up to cook from scratch so I had to learn how to cook meat from scratch and never out outside of the home. Also organic meat is relatively expensive, so it became a weekly treat. For years I’ve eaten meat containing meals two or three times a week with the majority of meals vegan or vegetarian. It turns out this could be the most sustainable diet we can have and mirrors how Britons ate for millenia.

I grew up at a time when traditional farming, mixed rotational farming, was in decline, yet in rural upland Wales it continued to an extent. I went to YFC events such as ploughing and hedging competitions, yet such skills as hedging [making hedges] were in rapid decline. However in places like the USA and Australia, small single family farms were fast disappearing, to create ‘mega farms’ of vast fields to produce food industrially with artificial fertilisers, pesticides and GM [genetically modified] seeds. Animals are managed indoors. This “modern” farming produces food at scales the small traditional farms could not hope to compete with commercially, as the new capitalism of Thatcher and Reagan demanded ever cheaper food to create capital. The hedgerows, trees and awkward parcels of land were “improved”/ destroyed to facilitate cheap production.

We are now at a point of crisis from climate change. Wider society is waking up to these challenges and meat production is seen as part of the problem. We are all responsible for the way we as humanity produce food. More and more people are going vegan as the way to at least do something about it. Yet this has produced a false dichotomy. Farmers being blamed for the food production system they’ve been forced into by the supermarkets and large corporations and vegans for reliance on unsustainable imported food. These arguments are a distraction from the real issue of what sustainable agriculture looks like.

If you look at a typical Mid-West US farm today, you will find vast fields of grain, watered by equally vast pivot irrigation systems, managed by vast heavy machinery such as combine harvesters with GM seeds with a special coating to provide the soil microbiology absent from the soil, with the cattle kept in vast sheds with the associated health issues, but we can keep developing expensive supplements to get around that. This system feeds the world but it is an incredibly vulnerable system, reliant on so many inputs and is increasingly expensive as new varieties of seeds and treatments are continually required to keep up with the pathogens, there is a whole multi-billion pound industry constantly developing new treatments. If this system goes, the world will starve.

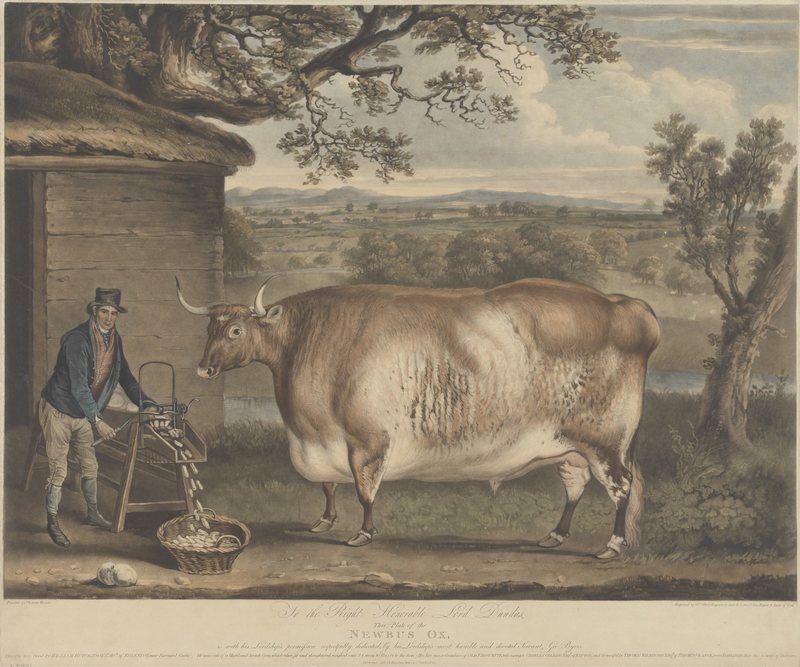

Contrast this with traditional farming. A traditionally managed field is rotated, one year it may have barley for winter feed for animals, another year vegetables for sale and winter feed, hay pasture for winter feed, pasture for grazing for a few years, a rest year. All the while, manure from the animals returns nutrients to the soil, the lack of heavy machinery restricts soil campaction, so a healthy soil is maintained, with a rich microbiota that can usually outcompete pathogens. Hedgerows maintain a niche for birds and insects who will also feed on pathogens. All with a farmer keeping an eye on things to make sure that nature is preserved but not taking over the fields from production, it’s a delicate highly skilled balancing act to produce enough food to sell to the rest of us. Yields are not as great, as some of the crop will be lost, more human labour is required making it less ‘efficient’. Yet it is a sustainable system.

Unfortunatly, even if we collectively decided that we wanted and needed this sustainability, it could not feed the world. The worlds population has increased massively over the past fifty years and we don’t have more land to get, there is none left. I think the farmers I knew growing up were sceptical of the changes and didn’t like losing their traditions, so this was why they had some sympathy with me, but were economically compelled to adopt some intensive practices and considered me the ‘lefty’ economically illiterate townie.

I almost hate that my concerns about food and farming have been perhaps correct. It’s not actually sitting uncomfortably on the fence, it’s simply a recognition that the dichotomy, the arguments we have on social media is a false one. If as a planet we cut out intensively produced meat and maximised arable production for human consumption, we could allow much much more sustainable agriculture. It’s not about giving up meat, livestock are an important element of the agriculture system. It’s for most people now, eating less meat, but when you do it will be more tasty, nutritious and more of a pleasure. A free-range chicken or grass fed cow contains much more essential micronutrients than the intensively produced one and has a rich taste with little need for additional flavouring. The traditional British ‘meat and two veg’ meal isn’t bland if you get traditionally produced food, it is full of interesting flavours. If we saw meat as a treat and as part of a sustainable system and had vegan meals for the mostpart, we would be progressing to a sustainable existence on this planet.

Sometimes I wish I’d have had the confidence to shout a little louder when I was younger.